Weaving My Dreams

"Library." For all this time I believed the term meant always a sober, high-ceilinged room with crown molding and Corinthian pilasters, the light kept filtered with wide-taped blinds, just like the Carnegie library in my hometown. Once upon a time it was the same for many Americans. Nobody went to low-ceilinged, unadorned, postwar "media centers."

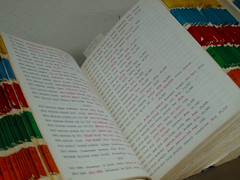

And so I kept envisioning the Paramount Theatre Music Library as some Beaux Arts structure improbably located in the Art Deco Paramount Theatre. Fantasies are stubborn. My other notion to revise cloaked the word "archive." For I knew I wasn't going to be part of a homely circulating library, where the nice lady at the main desk stamps the due date on the materials you hand her. I was convinced I would enter a sterile room full of light tables, temperature-controlled safes, and imperious archivists handing me white cotton gloves. But no, every Tuesday I just walk right in to a room of friendly volunteers, and I don't even supply a biometric.

If it sounds like PTML archival practices are informal, recall that, according to The Da Vinci Code, priceless ancient documents are kept unsecured in a church basement, with no concern for UV damage, humidity, or rodent control. So we're certainly better keepers of, say, Victor Herbert's "Whispering Willows," than the Priory of Sion.